Why Documentation?

Documentation as Servant – The Why and What of Documentation?

As discussed in the blog “Doing what you love”, many educators in the profession find the joy of their work is experienced through being with the children, organising the environment for the children and engaging with the team. Many educators are ‘people people’ and find the task of documentation is one of the less desirable aspects of the role. And whilst a rare few find satisfaction in a completed report, for many educators it can feel as though they are a slave to documentation requirements demanded by others, instead of a process that is a servant to their practice.

So why do Early Childhood Professionals document?

Several main reasons for undertaking documentation can be identified.

1. For the educator’s own practice.

During the course of a week, an educator may provide a program for tens of children. Relying on memory holds risk of forgetting, and prevents shared information with the educator team. Holding it all in your own mind can be useful as it allows prior knowledge and observations to contribute immediately to practice decisions, however if your teammates in the classroom can’t read your mind, they will not have access to important information. Educators may have different priorities for documentation, however these are some examples of the types of documentation that would support your memory and communication with the team:

- Upcoming plans such as cooking experiences, in order to ensure resourcing.

- Current interactional strategies with children, such as supporting a child to make friends, modelling language or providing positive moments.

- Cognitive progress information to allow for scaffolding such as counting with a child or inviting a child to try a particular activity.

- Reminders to observe children that may have flown ‘under the radar’.

- Assessing a child’s progress in accordance with Regulation 74. (Considering the E.Y.L.F and National Standards). Also see “The Child’s Progress” blog.

- Reflection on practice as a means of professional growth.

2. For meaningful partnerships with parents.

Parents as first teachers, provide amazing insight into the child, and can support practice at home to provide consistency of approach for children. Documentation to support this partnership is important and may involve discussions regarding the child’s interests and challenges, information about tasks tackled and achieved, and a way of making the day ‘visible’ to the parents.

3. To comply with the requirements of auditors.

The first two reasons have a direct and meaningful relationship with the educator’s purposes. In many circumstances, however, educators are undertaking ‘busy’ work in an attempt to comply with the real or imagined assessments they believe they will face. Service leaders may impose a system or standard in the belief that they are preventing a negative outcome in an audit process (such as A&R – Assessment and Rating), however if this isn’t meaningful for the educator, it may be creating an unnecessary burden.

As a part of reflective practice, educators should look at the components of the documentation that they undertake and examine whether these tasks fall into reason 1, 2 and/or 3. If a task is only relevant for reason 3, perhaps evaluate the reason for undertaking it.

Dr Marg Rogers of the University of New England has been vocal about a phenomenon she identifies as “Managerialism”. This is explored further in the blog entitled “Trust and Professionalism”, however this article gives a good overview: Managerialism is driving the crisis in early childhood education

Documentation that is for a system that doesn’t benefit the educator, the team, the parents, or ultimately, the children, is not an exercise that should be done. The process should be abandoned.

What should educator’s document?

Let’s do some maths. In just a morning session of around 3 hours an educator might find themselves in a class of 18 children, for example. During this 3 hour time frame, there might be some times when they interact or observe 5 times in one minute across the class group, and other times when they focus on one child for several minutes. In each of these observations, the educator will be interpreting and analysing what they see, and making a determination between several possible courses of action such as:

- Not worthy of further consideration

- Safe to allow the situation to play out

- Continue observing, it may escalate

- New skill noted in a child’s engagement

- Child requires assistance to learn skills in that area (note this for planning)

- Child demonstrates an interest (note this for planning)

- Dangerous situation, intervene

- Child is struggling, provide assistance.

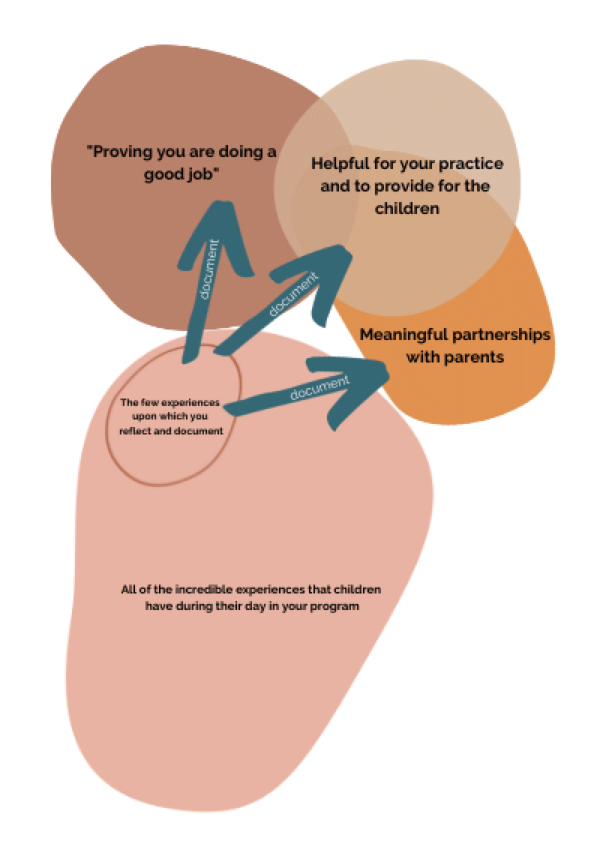

If we settle on an average of 3 such observations per minute, for 3 hours only (remembering that educators are with children often for 6-10 hours per day), the result is 540 observations. Of course it is a nonsense to even toy with the idea of documenting more than the merest sliver of this. The following graphic makes a picture of the decisions educators make each day:

In making the decision about WHAT to document, educators should evaluate the following:

- Is this a matter that would benefit from a follow up plan for the child’s development?

- Is this an interest that is going to assist the child to engage, and/or become a fascination for many in the class?

- Is this an area of concern that would benefit from further attention in the form of observations and/or planning?

- Is this something that it would be helpful for the parents to know for our ongoing partnership for the child?

- Does this make the program meaningfully visible to the parents?

- Is this something that the child would like me to note?

Making observational notes to target a certain number (e.g. 5 observations required per day) can lead to tokenism at best, or meaningless practice that wastes time. Knowing what is significant is part of the knowledge base of an educator’s training, and is an important capability to gain.

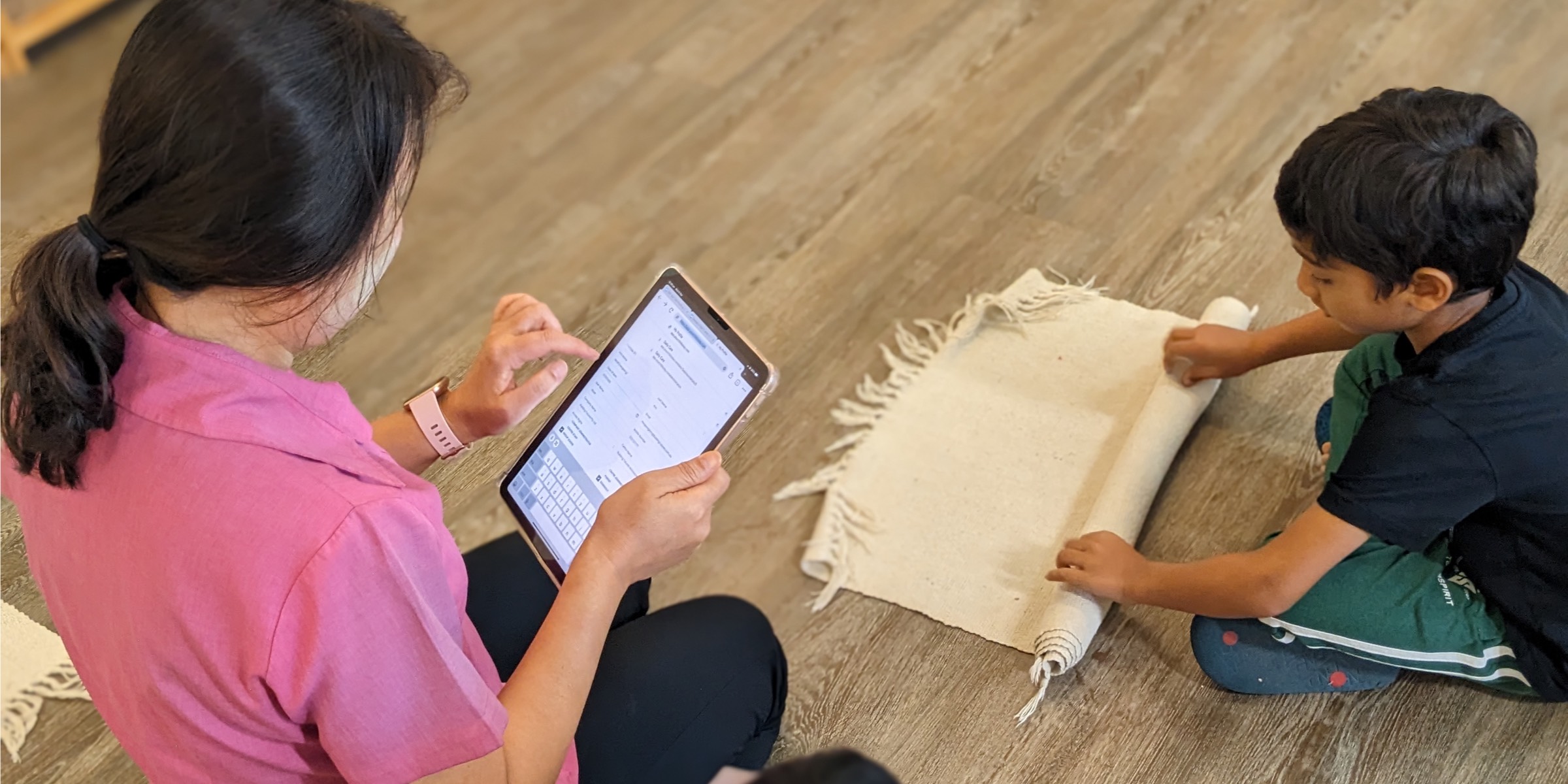

“Your Child’s Day” software is designed to allow Educators to very quickly record a child’s progress in only a few taps for those items contained within the activity library. This allows for the significant progress of a child to be captured seamlessly during the day, allowing non-contact time to be available for the educator to review, reflect, plan and research.

Helping children thrive is a shared journey. Spread the word and support fellow educators with insights and resources from Your Child’s Day.

Resources, advice, and uplifting stories for educators and families. No spam, ever.